It would be better if Augustus were never born or if he had lived forever. – Suetonius

Pessimists are usually right, but optimists change the world. –Inspirational calendar (August)

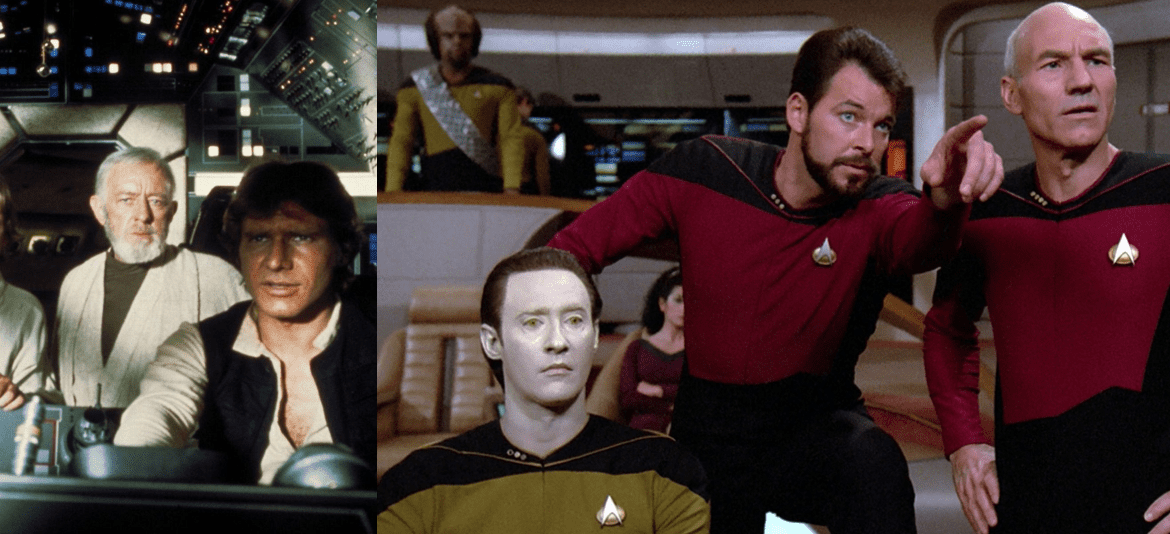

Visions of the Future When Establishing Analytical Culture:

Star Wars v. Star Trek

Let us briefly set aside our differences and discuss our space epics dispassionately. Star Wars and Star Trek have two of the most devoted fan bases, and while they may wish each other well, it is unusual to find fans devoted to both. Both have spaceships, alien races, and novel technology. However, the two franchises have a starkly different vision of the future (and don’t give me that “a long time ago business” – they have spaceships, technologically, it’s the future).

Star Trek – Idealism

Star Trek is fundamentally idealistic about the future. Humans have established gender equality, eliminate racism, and established as their Prime Directive a mandate for non-interference, mitigating the potential for the evils of colonialism (though this is typically violated for the flimsiest of pretenses). Technology in this universe is transformational and uplifting. Faster than light travel has established the capability for exploration and discovery. The replicator has ended any concept of hunger or physical scarcity and established instantaneous point-to-point travel. The conflict has certainly not been eliminated, but the struggles are typically between that of elevated humanity against a life-form at a different level of evolution, a culture with radically different values, or a throwback human rebelling against the greater good of all with selfish individuality – the last are typically punished or killed.

Star Wars – Decline and Fall of the Empire

Star Wars is essentially pessimistic about the future. There are lasers and spaceships, but the quality of life looks no better than now and perhaps worse. Any recognizable civilization is either a crumbling façade of a forgotten city-state, or a vast autocracy primed to eradicate individuality. The humans and aliens seem to have established hatred toward each other, but we’re just not familiar with what the races are. Technology is typically used to kill and does not even receive the hand-waving explanations in Star Trek. We are really meant to receive these advances as magic rather than the accretion of incremental progress over time. The future looks a lot like today and doesn’t provide any New Hope that civilization will get substantially better – smiling ghosts and teddy bears notwithstanding.

What Does it Matter?

It turns out this is a bedrock issue for managers. Do we fundamentally believe that large organizations can be forces for transformational improvement as they are in Star Trek, or do we espouse the Star Wars belief that the nature of crowds and power leave large organizations fundamentally corrupt or malevolent, rendering long-term improvement unachievable, the sole provenance of a force-infused rogue change agent?

This is already an emotionally charged subject, so let’s disentangle the love of the franchises from the implied worldview. On a personal level, I lean toward Star Wars and become even more biased if I forfeit Wrath of Khan on the basis that it is essentially a Star Wars-style movie with Star Trek characters (Spock forgive me). I might also admit that the Decline and Fall motifs of Star Wars feel increasingly realistic.

However, I am not a Jedi, I don’t know any Jedi, and I am unlikely to become a Jedi. I am but a lowly executive with above-average math SAT and a penchant for breaking things. The future that I choose to devote my efforts to is that consistent incremental positive change to affect long-term transformation. Does that make me a Trekkie – perhaps in an adult sense? Can any of us in the practice of technology, business, law, or medicine ethically choose differently?

Note: one may choose this path and still skip Star Trek V.

The Truth is Out There

I have been spoiled by a charmed career. I have seen the analytical promised land. Confusingly, this was during my first adult job, and I didn’t appreciate how rare the situation was. I thought every company based decisions on relevant data supporting plausible business cases. When I got into consulting and got to see a broad range of companies, I quickly found that this was a capability far more often sought than held. An analytical culture is a powerful but fragile resource that must be seeded, nurtured, and preserved. While it exists, the organization can perform magic, and it’s a great place to work.

American Airlines – A Remembrance of Things Past

I graduated college in a recession, which was both a blessing and a curse. The lack of opportunity gave me an unwelcome period of reflection to properly consider what I wanted to do. In college, I had been greatly attracted to finance because some relatively simple math could be used to frame billion-dollar, multi-year decisions in black and white. I had also never left the country. Twenty-two-year-old me considered that a finance position in the airlines would kill both the insignificance and cultural ignorance birds with a single stone.

I graduated college in a recession, which was both a blessing and a curse. The lack of opportunity gave me an unwelcome period of reflection to properly consider what I wanted to do. In college, I had been greatly attracted to finance because some relatively simple math could be used to frame billion-dollar, multi-year decisions in black and white. I had also never left the country. Twenty-two-year-old me considered that a finance position in the airlines would kill both the insignificance and cultural ignorance birds with a single stone.

That may have been the one and only time that I had a plan for a big decision and it came off. As a result of a recession, American Airlines had cut recruiting salaries and for the first time, they opened the door to hiring undergraduates into corporate finance. When I got the opportunity to interview, I had coincidently been thinking of nothing else and devoted myself to preparation maniacally. That and the limitation of alcohol intake during the sponsored welcome dinner proved to be a decisive advantage against the competing 22-year-old candidates.

My luck held though it took me a few months to realize it. I was placed in a group tasked with calculating the profitability of every passenger flight. This information was used to set schedules for the airline and served as the primary topic of monthly meetings at the executive level. The inputs to these calculations were ticket revenue on one side and the general ledger line items categorized into cost pools. The pools of cost were then allocated to individual flights based on operational systems monitoring flight statistics, fuel burn, pilot scheduling, etc.

On one hand, this was overwhelming, but on the other, it was an opportunity to put to use the statistics, accounting, and finance that I had long despaired of having a practical application. There was so much data available. All you had to do was get it and come up with an idea for how to use it. At that age and level of experience, I could do neither.

Leadership is Important

Fortunately, I had an incredible manager in David Roberts. He was a Kellogg MBA and a Cornell Masters of Engineering, an intimidating brain to say the least. However, he also had the generosity that is only available to those accustomed to being the smartest guy in the room. He pushed me to learn to code as a secret weapon. Being able to use that skill to access data got me on a lot of projects nobody my age should have been close to.

Data can do Anything

I also got to enjoy the company of MBAs from top programs, and they introduced me to libraries of theory in statistics, finance, and managerial accounting. Rich Coskey was a newly minted Cornell MBA that taught me that you could pull any of these theories off the shelf and code them into financial models to drive radically different decisions. You shift a couple of parentheses around, and hub-and-spoke scheduling doesn’t look like quite the positive innovation previously thought.

The point is, that I’m idealistic because I’ve seen the ideal. The two people I mention above stand for hundreds that I had the opportunity to work with. Out of every team of four, there was typically one person that could code, and all of them were pros in Excel. That meant for any significant project being considered, the profit impact could be evaluated. Operations were driven by real-time data and historical models, and performance was reviewed across multiple perspectives with consolidated data. New opportunities for optimization were sought and taken. That was the job description.

What does it look like?

American Airlines was the first company that I got to see from the inside, and naïvely, I thought all companies were like that. After working with hundreds of clients, I have a significant appreciation for how rare and fragile an analytical culture really is. It doesn’t have to do with industry, the age of the company, or geography—airlines have been around for a century; this one headquartered in Irving, Texas just happened to invent real-time computing. An analytical culture is something that must be painstakingly built and actively preserved. The rewards, however, are vast.

People are the Competitive Advantage

Every business is a talent business, it’s just a matter of degree. Consider the best bricklayer in the world. He can build four walls at the same time that a merely competent colleague can build one. In basic masonry, that person is in the hall of fame. In technology, however, one incredible person can do the work of hundreds, if not thousands, of moderately talented technicians. Are they harder to get? Sure. 100 times as hard? Probably not. Is your business more like masonry or technology? If it’s anywhere closer to the latter, you’ll never regret the investment you make in top talent.

That investment can be significant, and it’s not just sallies and bennies, though those must be competitive. Are you aware of the pipelines for talent for each of your functional areas? Do you have any relationships with them? Are there university programs for the fields you’re hiring? Do you make recruiting trips? Is your interviewing process rigorous and unbiased? Do you review the results? Do you encourage/mandate employees to move functions every 12-18 months? Is there a clear career progression? Do you have a mentor program? Executive development? Incentive and stretch goals/bonuses? Sabbaticals to prevent burnout? Each of these is an investment of time and/or money, and they’re critical to finding and keeping top talent. More importantly, these measures help to ensure that top talent makes it to the executive suite and populates the VP, director, and manager layers with rock stars.

Analytics is a Process

So, let’s assume you’ve done what you need to do to get great people. I’ve been in several organizations where the dream team was assembled, but let’s just say they didn’t always win gold. Culture is key, and it is a fragile thing. Here are a few elements that are pretty closely correlated with success.

Coding is Cool

Coding is a skill, not a job. Whether you’re in finance, marketing, or operations, the skills that you build up in college are enough to marshal data into better decisions. Getting or manipulating the data might require a bit of coding. Anyone that can write an Excel formula can write SQL. Unfortunately, most business programs teach the former but not the latter. Make these young whippersnappers get their hands dirty. It will teach them about the systems that run the organization and about the oceans of data ready to be mined. Not everyone will take to it, somewhere between 1-in-5 to 1-in-3. That’s ok. Not every marketing planning director needs to write stored procedures – but one person on a team that knows how to automate targeted campaigns based on customer data turns out to be a pretty good complement to the creatives. Consider what the organization looks like when every team in every function has someone like that.

Arguing is Cool

Arguing doesn’t mean you hate each other. If two or more people have different approaches to a project, that is gold. If the culture is such that the best business case carries the day, and the data to support that case is available to those in conflict, those arguments are the true work of the management layer. I have walked away from multiple arguments like those having lost and feeling better about the direction of the next few months. I have been in many polite discussions unsupported by data on either side where my blood pressure remained low but saw good projects crumble like sand.

Comfortable is not Cool – Move Around

Every new job is terrifying. It takes several months to learn enough about the function to make a real contribution, and it can be frustrating to leave a job right when you start to see that value. However, let’s say the target is to promote to manager in 3-5 years.

Which resume would you rather see:

- Five years of budget planning

- Contributory roles in finance, marketing, and operations with an understanding of the underlying technology in each function

Easy hire. Imagine that you have 10-100 people with the same resume within your organization applying for the position. Recruiting for opening positions was brutal, but the bench for managerial talent gets deep quickly.

There are a fair number of knock-on benefits. When managers have experience in multiple functions, they know who to collaborate with to complete multi-disciplinary projects (i.e., anything worth doing). You also have an army of managers that feel confident they can walk into any room and save a million bucks. Remember that bricklayer? There’s also something satisfying when the room one of your rock stars walks into has four more people with the same results orientation but different skill sets. Where else are they going to get that? Hey, we have a culture going on here.

Technology is the Force Multiplier

Technology is a funny thing. My first job that a sober adult would intentionally seek was on a team of four, sometimes five people. At one time, that team was a department of 500 very smart people. They had the same task we had, calculating the profitability of every flight and producing a digest of that analysis, only they did it without the use of spreadsheets or any sort of modern automation. Thanks to Excel, SAS, and the APL heroics of Tina Lattanzio, we got to take an hour for lunch and breaks for sheet cake on departmental birthdays. Most of our time was spent on how to improve the theory and process, i.e., value-added work (not to mention fun). Note: APL = a Programming Language . . . seriously.

The output of that process was the Flight Profitability Review, and it was cooler to carry around than a Blackberry in the year 2000 (ahem, analytics as a culture – early 90s style). It meant you were invited to a meeting with CXOs to promote/defend your performance.

Note: While cool and career-benefitting, attendance was not always pleasant, as the CEO was perpetually attempting to quit smoking and occasionally threatened those without ready explanation with cardiac impalement by nearby writing utensils.

In one form or another, this was de rigueur. In yield management, every team leader knew their markets by the week and had ample notice of event-driven tidal waves of demand. The concept of an AI-driven organization is in current parlance; I can vouch for seeing one in full-blown operation in 1995, and it may have been a decade old then. In maintenance operations, every bolt turned by every mechanic was tracked and maintenance schedules were optimized and shuffled to the latest bulletin. Underpinning all of this was an ocean of data, the largest non-military computer in the world, and a management class ready and able to use that data to improve operations and decision-making.

It didn’t matter what department or function; that was the expected operating mode. If you didn’t have data on your side, people would look at your askance. One would call it an analytical culture. The result of all of this is that a know-nothing 22-year-old was expected to produce the same value as 100 experienced analysts. With that technology, that culture, and those people, that was a Wednesday.

Conclusion

People without the culture or the technology are not enough. “A” players want to make their impact and they want to play with other “A”‘s, and if they can’t do something big at your organization, they will do it elsewhere. Technology without quality people or an analytical culture is not enough. Data does not act, is not shared, and certainly doesn’t organize itself into subsystems to optimize operations, though it may be a foundation to build a team on.

The culture by itself is just the C-suite’s vision of the future. When that vision is a continuation of the wrong people, broken processes, and inadequate technology, it will turn out to be accurate. When it’s optimistic, it can drive the commitment to build the team and give them the tools for success. That too tends to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Northcraft Analytics was born out of a desire to provide the tools required to foster an analytical culture within the IT organization. Too often, technologists are tasked with providing analytical capabilities for a line of business functions and receive a little budget for bringing those capabilities to their function. Using Northcraft Analytics to underpin a killer team with a supportive executive vision enables an organization to boldly go to the future of its own choosing.

Post Script

You may ask yourself; didn’t all of those airlines go bankrupt? All of the majors were in and out of bankruptcy after the deregulation in 1978 except American. America lasted from 1926 to 2011 and was finally pressured into bankruptcy by the reduced cost structures of the recently bankrupted and consolidated majors. Along the way, they invented Real-Time Computing (1960), and Yield Management (1979), a frankly superior pre-cursor to ARPANET/Internet (SABRE). The talent from America spread out across corporate America, including the C-Suite of AT&T, FedEx, Delta Air Lines, and Hawaiian, and those are just people I knew personally. AA alumni, please chime in in the comments to augment the list. An excellent book on the industry history is Hard Landing.